“The factory of the next decade will not buy more machines first; it will buy more print files.”

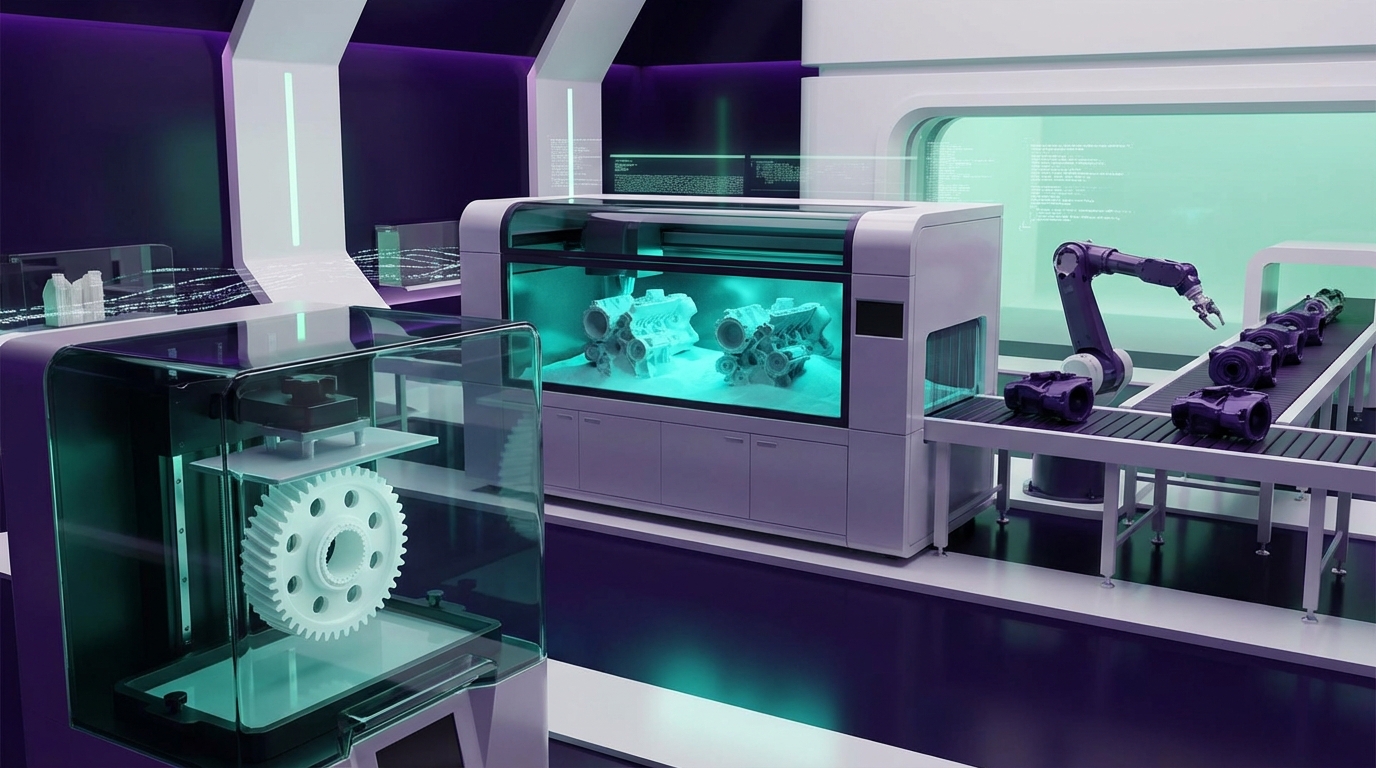

The shift is already visible on income statements: 3D printing moves from a cost center for quick prototypes to a revenue driver for short-run production, spare parts, and customized hardware. Manufacturers that treat additive as a core production method, not a side lab experiment, start to see double-digit margin gains on low-volume SKUs, faster time to market, and reduced inventory carrying costs. The trend is not clear yet across every sector, but the business value is no longer a hypothetical line in a McKinsey slide. It shows up in lower tooling budgets, smaller warehouses, and new SKU strategies.

Investors look for one thing in this space: proof that a factory can turn CAD files into saleable units with repeatable quality and predictable cost per part. When that happens, revenue per square foot of floor space goes up, working capital tied in stock goes down, and pricing power improves because customers pay for customization, not just volume. The logic is simple. Traditional manufacturing rewards scale; additive rewards complexity and responsiveness. Any plant that makes parts in many variants, with moderate batch sizes, now has to run a basic calculation: keep pouring capex into molds, dies, and machining centers, or shift part of that budget into printers, software, and powder management.

For years, the story around 3D printing lived in the prototype room. Designers printed a mockup, checked fit and ergonomics, and sent drawings off to be milled or cast. The printer was the intern of the shop floor. Cheap, useful, and ignored during budget season. That script is changing as material science matures and machine reliability improves. When aerospace firms start certifying printed metal brackets for flight, or medical companies print thousands of custom devices a month, procurement teams listen. They see reduced minimum order quantities, fewer suppliers to manage, and less exposure to geopolitical risk in complex supply chains.

The market indicates a gradual but firm migration from “print one part to test” to “print a thousand units to ship.” This is not hype. It is a response to two pressure points: demand volatility and product complexity. Shorter product life cycles mean that tooling amortization gets harder to justify. At the same time, customers want more variations: different geometries, lighter parts, integrated features. Traditional processes struggle when complexity goes up but volume per variant goes down. Additive flips that equation. Complexity is mostly a software problem. Change the file, not the mold.

Business leaders now ask a direct question: where does 3D printing slot into the P&L in the next five years? Is it R&D expense, or cost of goods sold, or even a service revenue line? The answer depends on sector and strategy, but the direction of travel is set. Hardware vendors push for higher throughput. Software vendors build MES connectors. Contract manufacturers advertise “additive lines” next to CNC and injection molding. The opportunity is not just technical. It sits in pricing models, supply chain redesign, and how a company measures ROI on capital spending.

“We stopped buying molds for any part with a forecast under 50,000 units a year. That single policy change paid for our printers in 18 months.”

From Prototype Room to Production Floor

The original pitch for 3D printing in manufacturing was simple: cut weeks out of the design loop. That still holds. A designer sends a file to the printer in the morning, holds a part in the afternoon, and fixes issues before any tool steel is cut. The value is clear and easy to quantify: fewer design errors, shorter development cycles, and lower tooling rework. Many plants treat that as “job done.” They stop at prototyping.

The interesting gains appear when a company asks a different question: if a prototype is good enough for functional tests, what does it take for that same process to be good enough for saleable parts? This is where standards, traceability, and process control move into the picture. The printer goes from “anyone can send a file” to “locked down, validated workflows” with material lots tracked, machine parameters logged, and quality checks embedded.

Investors look for this crossing point, because that is where margin profile changes. Once a printer runs production parts, its cost is spread over revenue, not just R&D. Utilization hours matter more. Maintenance schedules matter more. The printer becomes a mini production cell, not a toy.

“We treat each print bed like a micro factory. Same rules, same audits, same yield targets as any other cell.”

The path from prototype to production usually follows four steps:

1. Internal functional parts

Manufacturers first start printing jigs, fixtures, and assembly aids. These do not leave the building, so certification and surface finish demands are lower. Yet the business case is strong. Printed fixtures can be lighter, more ergonomic, and cheaper than machined ones. Changeover time drops when fixtures are modular and quick to redesign.

ROI in this phase:

– Lower fixture cost per variant

– Faster changeovers between product variants

– Improved operator ergonomics, which can lift throughput

2. Bridge production

Next, plants use 3D printing as a stopgap before full tooling arrives, or when demand spikes above forecast. This is called bridge production. It helps when a product launch runs hotter than expected or when a supplier delay threatens a line.

The business case here is risk mitigation. 3D printed parts cover the gap. Margins may be thinner on those batches, but the company avoids line stoppages, penalties, and market share loss at launch.

3. Low-volume / high-mix SKUs

After some successful bridge runs, procurement teams notice SKUs with chronic issues:

– Lifetime volumes too low to justify molds

– Frequent design tweaks for customer-specific versions

– High scrap levels from old tooling

Those SKUs are good candidates for permanent migration to 3D printing. The printer becomes the default process, not a backup. Engineering validates equivalent or better performance. Finance tracks per-part cost including depreciation and compares it against old tooling plus overhead.

4. Full serial production

The final stage is when additive runs as a core process for significant product lines. This is still limited to certain geometries and materials: orthopedic implants, turbine components, complex fluid channels, bespoke dental devices, some automotive brackets, and consumer products with high personalization.

Business value at this stage is not only cost per part. It includes revenue upside:

– Ability to offer custom variants at higher price points

– Faster introduction of design improvements without tooling delays

– Reduced risk of obsolete inventory for parts that change often

Where 3D Printing Fits in the Factory Economics

To make sense of 3D printing as more than a cool tool, we have to look at the core factory economics: fixed vs variable cost, batch size, lead time, and inventory.

Traditional processes like injection molding or die casting have high fixed cost (tooling) and low variable cost per part at scale. They reward large, stable orders. Additive reverses that profile: low or no tooling cost, higher variable cost per part, and strong sensitivity to volume per batch and machine utilization.

This creates a crossover point. Below a certain annual volume, printed parts are cheaper overall than tooled parts after you add tooling amortization, scrap, and inventory holding. Above that volume, traditional processes still win on pure cost per unit. The challenge for executives is to map each SKU against that curve.

Cost model basics

Consider two simplified cost models:

– Traditional:

Total cost = Tooling cost / expected units + per-part production cost + inventory costs

– Additive:

Total cost = Printer depreciation / capacity units + material + machine time + post-processing + quality

The additive model looks heavy at first glance. Machine hour rates are not low. Material cost per kg can be significant, especially for metal powders. Yet there are offsets:

– No or minimal tooling

– Lower scrap, because you print near-net-shape

– Less overproduction “just to fill the run”

– Lower inventory, because you can print closer to demand

When finance teams run side-by-side scenarios on selected SKUs, they often find segments where additive is already competitive or close. The economic gap narrows further when you add soft factors like reduced time to market or the value of on-demand spares.

From Capex Toy to Production Asset

Early 3D printing investments in factories were often capex rounding errors: a few machines in the R&D lab, justified as “we need to keep up.” That kind of purchase rarely changes how a company runs. To move 3D printing into production, leaders need to treat printers like any other production asset: develop utilization targets, maintenance schedules, and clear ownership.

Investors gauge maturity by a few signals:

– Is there a clear owner (operations or manufacturing engineering) for additive lines, not just R&D?

– Are print jobs integrated into the regular production planning system?

– Are yield, scrap, and uptime tracked against target?

Without that, printers sit idle, or they only churn prototypes. The ROI then looks weak, and management calls it a failed experiment.

Materials: The Real Gatekeeper

Machines grab headlines, but materials determine where 3D printing can earn a place in production. Plastic filaments and resins work for housings, fixtures, or low-stress parts. Metal powders and advanced polymers open doors in aerospace, medical, oil and gas, and automotive.

Material science also drives certification cycles. For a part to move into a regulated environment, the material has to show consistent properties: tensile strength, fatigue resistance, temperature stability. This is where partnerships between OEMs, material vendors, and standards bodies matter.

“The printer is just the delivery vehicle. We spend more time qualifying powder lots than we do arguing about machine models.”

From a business perspective, material availability and pricing matter. A factory that locks itself into a single proprietary material channel carries supply risk. C-suite teams now ask whether a planned additive program depends on a sole vendor or if multiple suppliers can provide compatible feedstock.

Then vs Now: Early 3D Printing vs Current Industrial Use

To see how far the technology has traveled from hobby corners to production cells, it helps to compare the early era with current conditions.

| Aspect | 3D Printing in 2005 | 3D Printing in 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Main use in factories | Basic prototypes, visual models | Functional prototypes, fixtures, end-use parts |

| Typical materials | Limited plastics, fragile resins | Engineering polymers, composites, metals, biocompatible materials |

| Printer reliability | Frequent jams, low uptime | Industrial uptime with preventive maintenance and monitoring |

| Quality control | Visual inspection; minimal data logging | Closed-loop monitoring, traceable parameters, automated inspection |

| Integration with factory systems | Standalone; manual job scheduling | Links to MES, ERP, and PLM; integrated planning |

| Role in supply chain | Local support, no impact on global supplies | On-demand spares, localized production, backup for supply disruptions |

| Business perception | Nice-to-have lab tool | Strategic process for selected lines |

Retro Specs: How Early Users Saw 3D Printing

Early commentary around 3D printing in factories had a very different tone. The expectations, worries, and language all reflect a time when the technology sat on the edge of serious manufacturing.

“We bought a 3D printer for the design office last year. It is great for mockups, but production will keep running on CNC and molding. Maybe that changes in ten years, but I do not see us printing thousands of parts any time soon.”

Manufacturing engineer, 2005 user review

Back then, the market focused on build speed and visible detail more than mechanical properties. Printers carried a reputation for being touchy and slow. The idea of qualifying them for aircraft or implants sounded remote.

“The machine is impressive, but the parts feel brittle. We use it to check shapes or for trade show models. For anything that takes real load, we go back to machined parts. The cost per prototype is acceptable, but I do not run a business case for production on this thing.”

Product designer in a consumer electronics firm, 2005 user review

These “retro specs” highlight two themes:

1. Material limits blocked serious structural applications.

2. The ROI discussion stopped at prototyping and did not move into production economics.

“Management bought the printer after seeing a demo. R&D loves it. Our factory foreman calls it a ‘plastic toaster’ and refuses to talk about making anything real on it. For him, a real machine has coolant, chips, and noise.”

Shop floor anecdote, 2005

That cultural gap still exists in some plants, but it narrows as printed parts prove themselves in the field and as younger engineers, trained with additive in school, move into operations roles.

Then vs Now: Legacy Phone Manufacturing vs Future Devices

To ground the shift further, compare how a classic mass-market device was built compared with how future hardware can be made when 3D printing plays a larger role.

| Feature | Nokia 3310 Era (around 2000) | Hypothetical iPhone 17 Era (mid 2020s) |

|---|---|---|

| Production philosophy | Huge identical runs; minimal variation | Multiple variants, faster refresh cycles, customization options |

| Use of 3D printing | Almost none in production; some in prototyping | Extensive use for fixtures, some chassis components, and custom accessories |

| Tooling investment | High upfront, amortized over millions of units | Still high for core components, but selected parts switch to additive to reduce SKUs and tooling complexity |

| Spare parts strategy | Large stock produced with same tools, stored globally | Mix of printed spares near markets and limited central inventory |

| Design constraints | Conservative shapes to keep tooling simple | More geometric freedom for thermal management, antenna routing, structural elements |

This comparison is not a claim that future phones will be fully printed. The economics still favor molds for tens of millions of units. The point is different: high-value, complex, lower-volume parts in that same device family can move to additive, and peripheral hardware such as accessories, mounts, or repair components can be printed close to demand.

On-Demand Manufacturing and Spare Parts

One of the strongest current use cases for 3D printing is spare parts. Many industrial firms sit on warehouses filled with slow-moving items. Each part ties up capital, needs climate control, and risks obsolescence if product lines change or regulations shift.

3D printing gives a different option: keep the CAD and process data, not the physical inventory. Print spares when an order comes in, either in-house or through a partner.

The business logic:

– Lower inventory carrying costs

– Less write-off of obsolete stock

– Shorter lead times for remote customers, if you print closer to them

– Extended service life for products where original tooling was retired

This model fits well for trains, heavy equipment, defense platforms, and industrial machinery. In some cases, the original OEM no longer exists, but a service provider can scan and print critical parts.

New Business Models for Manufacturers

3D printing in production also opens new revenue streams beyond hardware sales.

Digital spare parts libraries

Manufacturers can sell access to certified print files instead of shipping physical parts. Customers or authorized partners print locally on approved machines with approved materials.

Pricing models can be based on:

– Per-print license fees

– Subscription tiers for different part families

– Bundled service contracts that include rights to on-demand printing

For investors, this shifts part of revenue into software-like margins, with high gross margin per license and lower logistics cost.

Mass customization as a service

Companies can charge for product personalization. Examples include:

– Custom grips, mounts, or interfaces tailored to user ergonomics

– Branded or color-customized enclosures for B2B equipment

– Medical devices shaped to anatomy (hearing aids, dental aligners, prosthetics)

3D printing makes these custom variations operationally manageable, because the change happens in software. Factories can produce one-off units without retooling.

Contract additive manufacturing

Some manufacturers turn their own 3D printing capability into a service for others. When printers are not fully loaded with internal work, external jobs fill capacity. This creates a new revenue line from the same asset base.

The challenge is not to distract from core operations. Companies that succeed here either spin out a separate unit focused on contract printing or keep a clear allocation of machines between internal and external jobs.

Integration with Existing Processes

3D printing rarely replaces all traditional processes. Instead, it sits alongside them in a hybrid setup. The key is process integration.

Hybrid production lines

In many factories, a printed part still sees downstream operations:

– Machining critical surfaces for tight tolerances

– Heat treatment for metals

– Coating, painting, or plating

– Assembly into larger modules

That means additive needs to “speak the same language” as other steps: part numbers, tolerances, quality standards. Factories that treat 3D printing as a separate island struggle to scale it. Those that integrate it into the same engineering change orders, quality systems, and maintenance logs see smoother adoption.

Software and data

Additive creates rich datasets: layer information, sensor readings, machine parameters. Used well, this supports process stability and traceability. The challenge is data overload. Plants need clear rules on which data they keep, how they analyze it, and who acts on it.

A practical approach:

– Store full build data for regulated parts or high-risk applications

– Keep summarized quality and process metrics for routine builds

– Feed anomaly detection systems with live sensor data to catch issues early

Linking this with MES or ERP helps track cost per part and ties quality issues to specific jobs, materials, or time periods.

Regulation and Certification

Regulated sectors such as aerospace and healthcare move slower, but once a process is certified, it can scale quickly within that framework. Certification often focuses less on a single part and more on a “process envelope”: a validated combination of material, machine, parameters, and inspection steps.

From a business perspective, certification is both a barrier and a moat:

– Barrier, because the upfront work and audit process require time and money.

– Moat, because once certified, a company gains an advantage over competitors that have not gone through that process.

Investors like clear, repeatable certification frameworks, because they support predictable revenue from parts that cannot easily shift to lower-cost suppliers without requalification.

Risks and Limitations

The picture is not all upside. Executives weigh several limitations before betting heavily on 3D printing in production.

Cost per part at scale

For very high volumes, traditional processes still win on cost. A smartphone casing produced in the tens of millions will not move to additive any time soon under normal market conditions. Energy input per part, cycle times, and materials all favor conventional mass production.

This means 3D printing fits best where:

– Volumes are moderate

– Complexity is high

– Customization has value

– Tooling would be expensive or short-lived

Workforce skills

Running production-grade 3D printers is not the same as running a desktop unit. Operators need skills in machine calibration, material handling, and basic design understanding. Engineers must know design for additive manufacturing, which differs from design for casting or machining.

Companies that invest in training and cross-functional teams (design, manufacturing, quality) get better returns.

IP and security

When the product recipe lives in a file that can be emailed, intellectual property risk grows. This is a serious concern when digital spare parts models or remote printing networks come into play.

Mitigation answers include:

– Encrypted, time-limited build files

– Hardware-based keys on printers

– Contract structures that control where and how files are stored and used

Signals Investors Watch in Additive Manufacturing

For venture and growth equity in the 3D printing space, and for public investors looking at industrial adopters, some signals are more telling than press releases.

Utilization trends

High utilization on production jobs, not just prototypes, shows that a company has moved past experimentation. If additive lines run in multiple shifts, with documented throughput, the business value grows.

Revenue mix

Vendors in the 3D printing ecosystem often report growing shares of revenue from:

– Recurring materials

– Software and process control tools

– Long-term service contracts for machines

Manufacturers that use 3D printing internally might not break out additive revenue, but they can track product families where printed parts allow higher gross margin through customization or spare parts.

Supply chain redesign

A serious shift to 3D printing often shows up in procurement and logistics: smaller supplier lists, less air freight for spares, or new regional micro-factories. Investors ask for hard metrics: reduction in inventory levels, lead time cuts, and incident records where additive avoided a stock-out.

What Comes Next: Factory Files, Not Just Factory Floors

Looking ahead, the real story of 3D printing in manufacturing is not exotic materials or giant printers, although those matter. The deeper shift is that the primary unit of manufacturing becomes the validated print file plus process recipe, not just the physical tool.

Companies will maintain “tooling libraries” in the cloud: digital molds, fixtures, part builds. When they enter new markets, they will decide which of those files to send to local hubs. Capex decisions will include not just which machines to buy, but which digital process packages to license or develop.

Manufacturers that grew around heavy tooling mindsets now face a transition. Their core strengths in quality, process control, and supplier management still apply. The difference is that some part of that expertise moves into software and data. Investors will watch who can make that shift without losing discipline on cost and reliability.

The trend is not clear yet across every sector, but the direction is consistent: from prototyping to production, 3D printing moves closer to the center of how factories design, make, and support products.