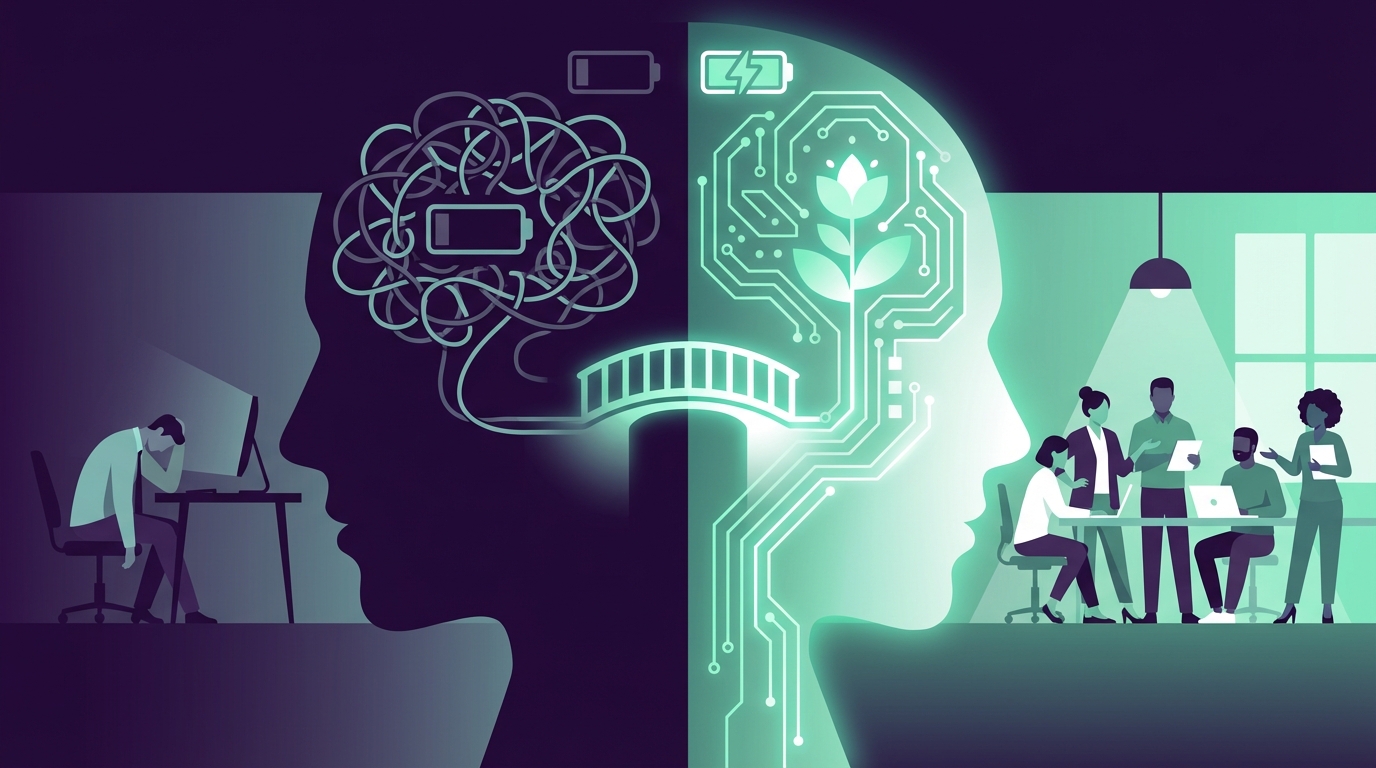

“If your dev team ships features at the cost of their mental health, you are not growing a company, you are burning capital.”

The market quietly started to price mental health into valuations years ago. You can see it in longer release cycles, calmer roadmaps, and founders who talk more about retention than raw headcount. Burnout in dev teams is no longer an HR problem. It is a revenue leak. A fatigued engineering org ships slower, introduces more bugs, and inflates cloud and tooling bills through rushed decisions. Investors look for predictable execution, and chronic burnout removes that predictability fast.

Mental health in tech is not just a soft topic. It shows up in churn, incident reports, hiring costs, and customer satisfaction. When senior engineers walk out, they take tribal knowledge, system context, and mentorship capacity with them. Replacing that is not a matter of a job post and a signing bonus. It takes months. The trend is not clear in every segment yet, but early data from public SaaS companies suggests that teams with stable engineering tenures and lower attrition tend to maintain higher gross margins and faster product iteration over time. The ROI of caring about burnout sits in these compounding gains.

Founders often say they care about culture, then reward only output metrics: tickets closed, story points, incidents resolved. The market makes a different judgment. When customer NPS drops after a messy release, when uptime slides, or when your product lags competitors by a release cycle or two, no one blames “the sprint.” They blame leadership. Burnout is a strategy problem disguised as a wellness issue.

Investors do not expect stress-free startups. They do expect sustainable throughput. That distinction matters. A team can sprint for one quarter on adrenaline. It cannot sprint for eight quarters without breaking. The history of high-growth tech is full of companies that over-optimized for short-term ship velocity and paid for it in rewrites, talent flight, or brand damage.

The hard part: burnout is hard to measure and easy to deny. Engineers will often push past personal limits to avoid blocking others or out of fear of being seen as weak. Managers are promoted for shipping, not for quietly preventing breakdowns. Boards rarely ask about on-call burden or psychological safety in retros. Yet when something breaks at scale, it almost always ties back to stressed humans making stressed decisions.

So the question for any founder or engineering leader is simple: what is the business case for protecting mental health in dev teams, and what concrete steps actually shift outcomes instead of just adding a meditation app and calling it “support”?

The economic cost of burnout in dev teams

Before talking fixes, it helps to quantify the problem in business terms. Burnout is often framed as “people being tired.” In reality, it behaves like technical debt in your org design.

“Burnout is people-debt with compound interest. You borrow energy now, you pay in attrition and rework later.”

From a tech journalist lens, three cost buckets stand out:

1. Attrition and rehiring costs

When a mid-level or senior engineer quits from burnout, you lose more than a salary line.

You lose:

– System context: why certain choices were made.

– Informal ownership: who everyone pings when a service misbehaves.

– Mentorship: how juniors ramp and learn safe patterns.

These pieces show up in productivity lag for the next 6 to 12 months. Recruiters often quote a hiring cost of 20 to 30 percent of annual salary. For experienced engineers in tech hubs, that is conservative once you factor:

– Recruiter fees or internal recruiter time.

– Interviewer time across the team.

– Onboarding overhead.

– Lower velocity while the hire ramps.

If your average engineer costs 180,000 dollars per year fully loaded, and you lose 5 burned out engineers in a 40-person team, you can push 500,000 to 1,000,000 dollars in hard and soft costs across a year. That money usually does not show up on a single line item. It leaks across slower projects, more bugs, and higher external contractor usage.

2. Quality, incidents, and customer trust

Burned out developers cut corners. Not because they do not care, but because their cognitive load is maxed out. They skip tests, accept “it works on my machine,” and defer documentation. That shows up as:

– More production incidents.

– Longer incident resolution times.

– Slower root-cause analysis.

Each incident touches multiple teams: engineering, support, customer success, sometimes legal. Hidden cost sits in:

– SLA credits or refunds.

– Canceled contracts from large customers.

– Teams pulled away from roadmap work to fight fires.

A stressed team also becomes more risk-averse in the wrong ways. They avoid refactors and foundational work that could reduce future load, because they cannot imagine taking on more risk. That pushes real risk into the future, the same way unaddressed technical debt does.

3. Productivity drag and missed upside

Founders tend to ask: “If we slow down to protect mental health, do we lose speed?” The data from real teams suggests a different pattern. Sustainable pace is what keeps velocity stable.

Google’s long-running “Project Aristotle” work on teams showed that psychological safety was the strongest signal of high-performing teams.

“Teams with high psychological safety had higher revenue, retention, and reported more joy at work, with no trade-off on delivery speed.”

Burnout cuts into flow state, the period where engineers do deep work. Context switching between tasks, pings, and incident channels kills this state. You pay for that with:

– More time per feature.

– More regressions from partial understanding.

– More meetings to sync up scattered threads.

The opportunity cost is sharpest in product-led growth companies. If your engineers spend half their time recovering from crunch cycles, they have less energy for experiments, small UX improvements, or performance tweaks that raise conversion and retention.

When you frame mental health within these costs, it changes the leadership lens. The question stops being “Should we care?” and becomes “Where are we overpaying for short-term speed with long-term drag?”

How tech culture set up burnout as a feature, not a bug

Tech did not end up here by accident. There is history behind the grind culture that still shapes many dev teams.

From garage myth to 24/7 Slack

In the early consumer web wave, stories about founders coding all night in garages helped raise money. Long hours looked like commitment. That narrative scaled poorly when venture-backed companies started hiring hundreds of engineers and layering in global customers.

The tools changed the expectations:

– Always-on chat (Slack, Teams) blurred “online” with “available.”

– Global customers normalized 24/7 incident response.

– Remote work erased office closing time.

What started as “we ship fast” slowly turned into “we are reachable all the time.” Without clear guardrails, that pressure moved into every level of engineering.

“The hero engineer who saves every incident at 3 a.m. becomes the performance bar for the whole team, even if no one says it out loud.”

There is also a strong identity piece. Many engineers love coding. They enjoy hard problems. That passion makes it easier for companies to normalize unhealthy norms. When the work itself feels rewarding, it is harder to see when rest is missing.

Agile rituals, unhealthy in practice

Agile, Scrum, Kanban, all aim for transparency and consistent delivery. The frameworks are not the problem. The way many companies apply them is.

Common dysfunctions:

– Sprints become hard commitments instead of forecasts.

– Velocity becomes a target instead of a measurement.

– “Stretch goals” become expected baseline.

This creates a constant micro-crunch every two weeks. The team hits the sprint goal by working late “just for this cycle.” That story repeats across months. No one sets out to burn people out. It creeps in through a series of small, reasonable compromises.

When you talk to burned out engineers, they rarely point to a single bad week. They describe an ongoing, low-grade pressure that never lets up. Over time, that pressure reshapes how they think about work, rest, and even self-worth.

The remote work paradox

Remote work solved some stress: long commutes, noisy offices, rigid hours. It created new ones.

Common remote stressors for dev teams:

– Time zone spread: meetings at awkward times.

– Uneven communication: some people live in Slack, others vanish.

– Visibility anxiety: fear of being seen as “not working” if offline.

Many devs report working longer hours at home, not shorter. They check status messages late at night, join “just one more call,” or reply to pings while with family. The line between work and life gets fuzzy. Stress becomes ambient, not acute.

From a business angle, this means leaders cannot just say “We are remote, so people have more freedom.” Without clear expectations, remote can amplify burnout under a friendly label of “flexibility.”

How burnout shows up in dev teams before people quit

If you want to manage burnout like a business risk, you need early indicators.

Behavioral signals on the team

Some common patterns in dev teams approaching burnout:

– Meeting participation drops. People show up, camera off, speak less.

– Code reviews slow down. PRs sit for longer, comments get terse.

– Learning stops. Engineers who used to explore new tools stop experimenting.

– Blame increases. Postmortems start to feel defensive instead of curious.

These are human indicators, not metrics. A manager who spends time in the code and in 1:1s can often sense the shift months before anyone resigns.

Quantitative signals in engineering metrics

No single metric will scream “burnout,” but combinations can tell a story:

– Incident volume climbs while incident response time increases.

– Lead time for changes grows even though team size stays flat.

– Reopen rate on tickets rises, signaling rushed or low-context work.

– PTO usage skews: some people never take time off, others disappear in long blocks after crunch.

If you have tools like Linear, Jira, or Git analytics, you can track how often work gets carried from one sprint to the next. Persistent carryover can signal that planning ignores human limits.

Cultural signals in conversations

Listen for recurring phrases in standups and retros:

– “I will catch up tonight.”

– “I can probably squeeze that in.”

– “I will take care of it over the weekend.”

Once or twice is normal. When these comments become routine, your team has started to define commitment as stretching past healthy limits. That pattern erodes trust in any stated “no weekend work” policy.

What actually works: structural fixes, not perks

Many companies respond to burnout with surface solutions: yoga sessions, meditation apps, swag. Those can help individuals, but they do not fix the system that creates burnout.

From a business angle, the most effective moves change how work flows through your engineering org.

1. Set hard constraints on time and on-call

Constraints create trust. A clear rule like “no deploys after 4 p.m. local time” removes pressure to push risky changes late. Guardrails that help:

– Fixed quiet hours: times where no meetings and no non-critical pings happen.

– Clear on-call rotations: no one on-call more than a set number of nights per month.

– Recovery expectations: anyone who handles a night incident can take recovery time without friction.

Teams that implement “no meeting Wednesdays” or daily focus blocks often report faster deep work. This is not about being nice. It is about protecting the mental bandwidth you pay for.

2. Plan for capacity, not just ambition

Roadmaps often ignore the human capacity side. They assume that if something must ship, it will. That mindset shows up in over-full sprints and constant re-prioritization.

A healthier approach:

– Track maintenance and unplanned work as first-class citizens in planning.

– Reserve a percentage of capacity for operational work: bug fixes, small improvements.

– Treat bugs and incidents as part of the workload, not as extra tasks “on top.”

A team that knows only 60 to 70 percent of its time is available for new feature work can plan honestly. That honesty is what protects weekends and evenings.

3. Redesign on-call to be sustainable

On-call is one of the fastest burnout drivers. Investors and customers expect strong uptime, but there are ways to meet that expectation without grinding your team down.

Key levers:

– Rotate fairly and predictably. No “informal” heroes who take extra shifts.

– Automate what you can: alert noise reduction, runbooks, auto-remediation.

– Compensate realistically: pay, time off, public recognition.

Run regular incident reviews that look not only at technical root causes but also at schedule patterns. If certain services cause repeated 3 a.m. incidents, that is a signal to invest in reliability. Every dollar you spend on making systems boring at night pays back in human energy.

4. Limit work in progress

Context switching is mentally taxing. Many devs juggle 4 to 6 tickets at once. That pattern looks productive on a board but feels draining day to day.

Borrow from Kanban and set WIP limits at team and individual levels. For example:

– No more than 2 active tickets per engineer.

– No more than X epics in progress for the team.

This pushes harder prioritization: you pick what matters and say no to the rest. From a mental health angle, it allows devs to finish work and feel closure. From a business angle, it reduces half-done features and improves throughput.

5. Give managers the tools to talk about mental health

Many engineering managers come from individual contributor paths. They know systems, not therapy. Expecting them to handle burnout conversations without support is risky.

Useful support includes:

– Training on how to ask about workload and stress without prying.

– Clear escalation paths when someone needs professional help.

– Manager metrics that count retention and team health, not just delivery.

If your promo criteria for managers only highlight ship dates and roadmap hits, they will prioritize output at all costs. If you recognize managers who retain talent, grow junior devs, and keep on-call sane, those behaviors spread.

Business value of mental health programs that are more than perks

Not every mental health initiative has the same impact on ROI. Some are symbolic. Others meaningfully change outcomes.

What founders typically try

Common efforts in startups and growth companies:

– Subsidized therapy or coaching sessions.

– Meditation or wellness apps.

– Company-wide days off.

– Mental health channels in Slack.

These can help individual employees, which has value on its own. For the business, the impact depends on how integrated these moves are with day-to-day work norms.

If engineers still get paged on “mental health days,” the signal is mixed. If therapy is offered but schedules leave no time to attend without guilt, uptake will be low.

Programs that tie directly to engineering outcomes

Here are patterns that tend to show tighter links to performance:

– Scheduled recharge cycles after intense projects. For example, a team spends 2 weeks in light maintenance after a major launch.

– Protected learning time. One afternoon per sprint for skill-building or experiments.

– Clear expectations on availability. “We do not expect Slack replies outside 9 to 5 local time, except on-call.”

The business value shows in:

– Lower incident rates and faster resolution.

– Higher retention rates for senior engineers.

– More internal mobility: devs move across teams instead of leaving the company.

This is where mental health links to growth. When engineers feel safe to stay, you keep domain knowledge, reduce rehiring churn, and maintain feature velocity.

Retro specs: how burnout looked in 2005 vs now

To see how far tech culture has moved, it helps to look back at how dev work felt in the mid-2000s compared to current cloud-era teams.

“In 2005, if the production server died at 2 a.m., someone might drive to a data center. In 2025, 2 a.m. is just another Slack ping in a global incident channel.”

Workload and expectations, then vs now

| Aspect | Mid-2000s Dev Teams | Current Cloud Dev Teams |

|---|---|---|

| Deployment frequency | Monthly or quarterly releases, big cycles | Daily or continuous deployment to production |

| On-call model | Small ops group, devs less exposed | Dev teams own services in production, frequent on-call |

| Tooling | Simpler stacks, fewer external services | Complex microservices, many dependencies and vendors |

| Communication | Email, IRC, in-office meetings | Slack, Teams, endless async and sync channels |

| Visibility into work | Local perception, less granular tracking | Burndown charts, dashboards, detailed analytics |

| Remote work | Mostly in-office, clear physical ending to the day | Hybrid or remote, weaker separation between work and home |

In 2005, burnout often came from death-march projects: long months leading up to a major release or client deadline. The stress pattern was spiky. People knew they were in a crunch. They expected a slower phase afterward, even if it did not always arrive.

Now, many dev teams live under steady, ongoing pressure. Releases are constant. Customers expect issues resolved in hours, not days. The stress pattern is flatter, more chronic. That makes it harder to see and easier to normalize.

Nokia 3310 vs iPhone 17: user stress mirrors dev stress

The devices themselves tell a story about workload expectations for both users and devs.

| Feature | Nokia 3310 (circa early 2000s) | iPhone 17 (projected modern flagship) |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | 2G, SMS and calls only, limited notifications | 5G/6G, constant push notifications, always online |

| App ecosystem | No app store, simple built-in apps | Millions of apps, complex SDKs, constant OS updates |

| User expectation of uptime | Basic network outages tolerated | Near-constant uptime expected for all apps and services |

| Update cycle | Rare firmware updates, via service centers | Frequent OTA updates, security patches, feature drops |

| Developer mental load | Limited devices and configurations to support | Huge device matrix, OS versions, regions, compliance rules |

As user devices became more capable, user expectations followed. Every push notification, every real-time feature, every always-on integration has a cost on the backend teams that support it. Burnout is partly the shadow of this complexity.

User reviews from 2005 vs now

Read software or phone reviews from 2005 and compare them with app store reviews today, and you can feel the expectation shift.

“2005 forum review: ‘The app crashed a few times, but the features are helpful. Looking forward to the next CD update.'”

“2024 app store review: ‘One crash during a payment and I am uninstalling. This is unacceptable.'”

The tolerance window narrowed. That tighter window reflects in how dev teams plan, test, and respond. A single missed edge case can trigger thousands of angry users in hours. That accelerates feedback loops but also pushes teams to treat every issue as urgent, feeding burnout if not managed carefully.

Practical playbook: where to start if your dev team is already tired

For founders, CTOs, or VPs of Engineering who read this and recognize their reality, the important step is to pick moves that show real intent without crashing delivery.

1. Run a psychological safety and burnout survey

Keep it short, anonymous, and practical. Focus on:

– Clarity of expectations.

– Workload perception.

– Safety to raise concerns.

– On-call and incident stress.

Share the results with the team and commit to 2 or 3 changes, not a giant transformation. This demonstrates that feedback translates into action.

2. Fix one structural stressor in the next quarter

Pick a high-impact, contained change. Examples:

– Clean up alert noise and on-call handoffs for one crucial service.

– Reduce the number of parallel projects per squad.

– Remove recurring late-night deploys by adjusting release windows.

Then measure:

– Incident volume and resolution times.

– On-call satisfaction in follow-up surveys.

– Any changes in feature delivery speed.

When the data shows equal or better throughput, it becomes easier to justify further changes.

3. Publicly back manager decisions that protect boundaries

If a manager moves a deadline to avoid weekend work, and leadership quietly punishes that move, every written wellness policy loses credibility.

Founders and execs need to:

– Praise realistic planning in all-hands.

– Share stories of projects that slowed a little and shipped more reliably.

– Avoid glorifying heroics that came at the cost of well-being.

Culture is shaped by what stories get repeated and rewarded. If the only heroes are the people who pulled all-nighters, burnout will keep spreading.

The investor lens: why mental health now affects funding narratives

Investors rarely ask directly, “Is your team burned out?” They ask broader questions that probe your ability to execute over time:

– “How stable is your engineering leadership?”

– “What is your current hiring plan and ramp time?”

– “How do you manage technical debt?”

Burnout creeps into the answers:

– High leadership churn suggests instability.

– Constant need for more heads suggests unsustainable processes.

– Heavy technical debt often traces back to rushed choices.

Funds that study org health see patterns. Companies with lower attrition and more stable squads tend to hit product milestones closer to plan. That reliability is valuable, especially in markets where capital is more cautious.

When pitching, founders can now credibly position their mental health and sustainability practices as risk management:

– Predictable delivery.

– Lower hiring volatility.

– Stronger customer trust through fewer outages.

The jargon matters less than the story: “We protect our dev teams’ energy so that we can ship quality product quarter after quarter.” That line is no longer “soft.” It links to margin, retention, and valuation.

Where this trend might go next

The trend is not clear yet, but early signals point to a few likely shifts in the next 5 years for dev teams and mental health:

– More transparency on workload in job postings: clear on-call rotation details and expected hours.

– Tooling that measures cognitive load: systems that warn when an engineer is pulled into too many repos, projects, or incident channels.

– Board-level metrics on people stability: tenure, internal moves, burnout risk indicators sitting next to revenue and churn.

Founders who move early on this will have an edge in recruiting senior talent. Many experienced engineers now select roles not only based on tech stack and comp but also on how the org treats mental health.

Protecting mental health in dev teams is not charity. It is a long-term growth strategy. The companies that treat it that way will quietly out-ship, out-hire, and outlast the ones that still equate exhaustion with commitment.